Information on Academic Writing

During your studies, you will have to do a number of academic examinations in order to gain credit points. These include, but are not limited to, presentations, essays, written exams, term papers, and, above all, the Bachelor thesis.

For general advice regarding academic work processes, information on in-class presentations, and formal requirements please consult our Style Guide. The criteria for marking term papers and presentations respectively can also be found online. In general, students have to enclose a declaration of originality with each examination, which can be found in the style guide's appendix. This does not mean, however, that term papers, presentations, and the like cannot be proofread by friends or family prior to submission. Far from it, we explicitly recommend having papers and presentations proofread which have to be in English. Below you find further information and advice regarding academic writing beyond these introductory remarks.

- On good academic practice

- Citation

- Phases of academic writing

- Building a line of arguments

- University library and Citavi

On good academic practice

Academic pursuits concentrate on one or several inquiries connected with each other and offer a solution for the presented problem. This solution makes use of already existing knowledge and attempts to generate new knowledge by connecting what is known with the students’ personal resources. Participation in academic discourses results from the use of primary (e.g. novels, films, advertisements, etc.) and secondary sources (e.g. articles or monographies), which are placed in the context of the respective inquiry, and connected with each other and the students’ own thoughts.

Academic writing is a way of scientists to connect and communicate with one another, often even beyond national borders, which entails that several conventions have to be heeded. Cultural Engineering students are offered a tutorial at the beginning of their academic career which aims at familiarising them with several basic principles of academic work. Additional competencies can be acquired over the course of their studies in the competency field (D): The PM 45 module "Academic Identity and Conduct" conveys the theoretical basics for interdisciplinary academic work.

Hermeneutics

Academic writing in social sciences is predominantly organised around a line of argument in the hermeneutic tradition, i.e. the answer to the questions is derived by connecting arguments logically. The individual arguments have to be supported by evidence. Evidence can either be generated by the students themselves, for instance by analysing a primary source, or refer to the work of other scientists. In this case, referencing has to adhere to certain conventions of citation.

Citation

There are many different styles of referencing but they all have one thing in common: The are supposed to ensure that ideas from someone else are marked accordingly. In this sense, citation serves as academic copyright’s quality management, so to speak. Moreover, citing sources helps other scientists to access their colleagues’ ideas. Over time, different disciplines have established their own styles of reference which, nonetheless, can be roughly differentiated into two kinds:

- In-text systems

- Footnote/endnote systems

Footnote/endnote systems are common in technical and natural science disciplines. Handbooks for these kinds of citation styles are, among others, the Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) or the Oxford Style of Referencing. In contrast, social sciences and humanities disciplines generally tend towards in-text citations, which refer to a list of works cited at the end of the work in question. The use of footnotes is, broadly speaking, not recommended. These styles of reference include, for instance, the Vancouver system, which enjoys great popularity in medical disciplines, the author-date citation of the American Psychological Association (APA), which is disseminated widely in the social sciences, and the style of the Modern Language Association (MLA), which is preferred in the humanities.

Most university chairs or instructors have their own preference with regard to the particular style of reference they want students to follow. When in doubt, consistency is key: The conventions of any kind of referencing are to be followed throughout the entire paper or presentation.

In the Cultural Engineering programme, the MLA style is preferred, as it is a style of references which is well-established in international cultural science research. In this regard, please adhere to the formal conventions as spelled out by our Style Guide. Information about the MLA style of reference can be found on the association’s website and in the official MLA handbook. In addition, many MLA guidelines circulate on the internet. These are, however, to be treated with caution and students are always well advised to check their origin diligently. Reliable sources are style sheets of other universities or the overview provided by the Purdue Online Writing Lab.

Phases of academic writing

Perhaps slightly misleading, the term “academic writing” encompasses far more than the actual writing. Academic work processes develop from preparation to making preliminary outlies and writing several drafts to the final writing process and ends with editing the final draft and tending to the layout. The preparatory phase includes, as a general rule, settling on a topic and researching most of the necessary literature. Having an overview over already existing literature allows to work out a concept of the paper, which can be transformed into an outline. The paper’s structure, however, should not be regarded as being set in stone but grows and alters together with the entire paper. Nonetheless, having a basic structure prevents losing yourself in the process and gives the paper a common thread.

Developing a basic structure, the outline, is followed by preliminary drafts which are supposed to indicate whether the devised structure proves conclusive and sensible and where it needs alteration. The actual writing is the iterative process of devising the different chapters, writing and rewriting them until you arrive at the final draft. Quite often it is this iteration which brings to light logical connections between different chapters or parts of chapters which you did not envision before. It is important to note in this regard that researching literature should not be entirely divorced from actually writing the paper. While it is necessary to begin the research process with searching for and reading existing literature, new thoughts and altered inquiries demand that you constantly update their choice of sources.

After having arrived at a final draft, the last phase begins. If you did not take care of the layout at the beginning of the writing process, you should do it now. But even if you have worked with the required formatting from the beginning, you are well advised to check the entire paper for inconsistencies as to ensure uniform line and paragraph spacing, typefaces, font size, title layout and avoid wrap errors.

Building a line of arguments

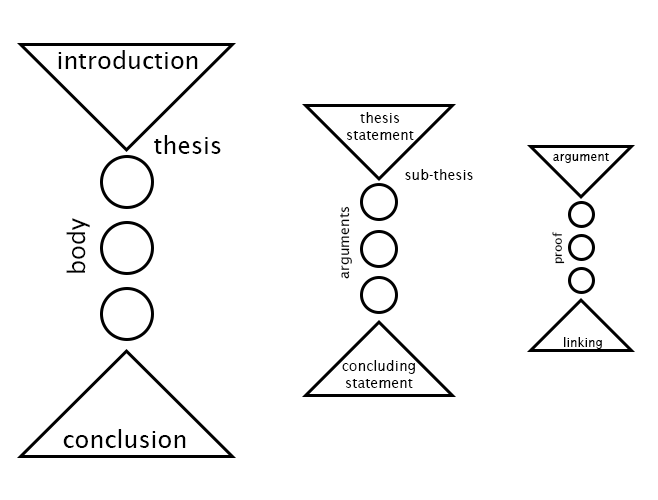

Academic papers and presentations can be tackled with different methodology while simultaneously heeding prescribed criteria. The so-called hourglass model is a trusted approach, which offers a reliable structure especially to those students at the beginning of their academic career. Finding a topic is the starting point of any kind of academic work: What do you want to write about? Once the topic is set on, it warrants narrowing it down and arriving at a thesis. The thesis is the narrowest point of any paper, visualised in the model by the tip of the upper triangle. The process of narrowing down the topic is mirrored in the introduction: It proceeds from the general topic to the precise thesis statement and thus provides readers with an entry point into the paper.

In the body of the paper, you have to argue for your thesis statement. The arguments should also follow a logical structure and be ordered accordingly. Every argument forms its own hourglass: Starting from the overall thesis statement, a sub-thesis is developed and supported with evidence. All arguments should be relevant to proving the overall thesis statement. This approach structures the paper (the often called-for “common thread”) and prevents you from losing yourself in the depths of your topic and writing an utterly incoherent paper.

The conclusions form the “bottom” of the hourglass. Starting from the thesis statement and the arguments and evidence in your paper’s body, you now have to return to the larger topic. Reflect on your thesis statement and the line of argument from your body. Explain which results arise from your paper. Why do you think your work is relevant? Where are linking points for other scientists? Moreover, drawing conclusions give you the opportunity to point out where your paper had to leave gaps which should be closed elsewhere. However, be careful not to destroy your own paper, but rather point to the disadvantages of your methodology (the advantages should already be included in your methodology chapter), or explain that you would have needed more resources to arrive at a more conclusive result.

The hourglass model shows how the three main components of your paper should link to each other in order to support your line of argument. The process of tracing the development of your thesis statement in the introduction is mirrored in the conclusions part, which links back to the larger topic. Thus, the introduction and the conclusions part frame your paper’s body, in which you develop your line of argument in order to support your thesis statement with analytical evidence.

University library and Citavi

The university library should be the first place to go to for researching literature. Moreover, the library offers regularly workshops and advice for, among other topics, using databases for research purposes, formatting academic papers, battling procrastination, or trainings for using Citavi. Citavi is a well-established programme to manage literature. OVGU students can use Citavi for free under the scope of a campus licencing contract after registering with the university computing centre.